Trust the Process?

Trust Is Earned. Transparency Is the Price.

It’s the new mantra.

“Trust the process."

A perfectly polished PR slogan—designed not just to rally support, but to squash dissent under the illusion of unity in the MAHA movement.

Echoed by social influencers, celebrities, wellness experts, and carefully orchestrated media partnerships—it’s MAHA’s version of "Just Say No" and "Stay Home, Save Lives". Say it enough, and people will believe it.

The reasons for the parroting are simple: MAHA wants support. They want an army of warriors backing RFK, Jr.’s decisions within HHS — and dissent is perceived to add resistence to the MAHA agenda.

Granted, the agenda may be noble—making people healthier—but noble intentions don’t excuse flawed execution. Corruption of processes created this crisis in the first place. Social desirability doesn’t override the need for rigor, transparency, and accountability.

They want us to just “trust the process” and “wait and see”.

The problem is trust is earned.

👉🏻Not through blind faith.

👉🏻Not through vibes.

👉🏻Not through celebritites and showmanship.

Trust is earned through accountability, transparency, and demonstrated results.

“Trust the proccess” requires having a transparent process.

In public health, we don’t build trust by hiding the blueprint. We build trust by showing the steps—by revealing the assumptions, engaging in meaningful dialogue, debating the trade-offs, understanding the data, and explicating a comprehensive plan.

You can’t trust a spouse who never communicates.

You can’t trust a government initiative that operates behind closed doors.

And yet, that’s exactly what we’re being asked to do.

We’re expected to believe that somewhere, someone has a plan. But what we’re shown is not a process—it’s a grab bag of disconnected announcements and tech-driven initiatives presented as if strategy can be reverse-engineered through PR.

If we truly want this movement to succeed, we mustn’t just trust. We must act as critical friends—offering support while asking the hard questions. Which brings us to today’s rabbit hole:

What would it actually take for me to trust the process—and mean it?

Let’s jump in. 🐇🕳️

Gold Standard Science, Bronze-Age Implementation

We heard it during the COVID era: Trust Fauci. Trust the CDC.

Trust the science. Trust the experts.

Now it’s back again, only with a new cast: Trust MAHA. Trust the wearables. Trust the registries. Trust the next press release. Trust the process.

The implication is clear: if we’d just trust more, the system would work — public skepticism, not broken systems, is what’s standing in the way. Our lack of trust is seen as an obstacle to MAHA’s progress.

The problem with this assumption is that the real obstacle to ending chronic disease in the nation isn’t public distrust—it’s institutional behavior that isn’t trustworthy. That’s a crucial distinction. Trust isn’t a personality trait; it’s a logical response to conditions. And right now, those conditions aren’t being met.

Influencers repeating slogans don’t build trust.

👉🏻Accountability does.

👉🏻Transparency does.

👉🏻Consistency between what’s promised and what’s practiced does.

MAHA was built on a promise of “gold standard science” and government transparency. Yet, when it comes to systemic change and the practice of of health system reform, the leadership isn’t walking the walk. They promote evidence-based interventions, yet fail to apply those same evidenced-based standards to their own decision-making and implementation processes.

Here’s the reality:

In public health, it’s not just what you do—it’s how you do it that matters.

Even the best ideas will fail if they’re implemented through corrupt, politically-driven, or opaque processes. As implementation science consistently shows, poor execution—not flawed ideas—is the primary reason good ideas fail to make a change.

We’re watching a pattern play out time and time again—where flashy announcements and private partnerships overshadow the real work of reform. The same broken systems that failed us in the past are still at the wheel. Whether it’s wearables, vaccines, or food safety, when the process is compromised, outcomes suffer—no matter how visionary the goals or utopian the promise.

Knowing what needs to change and knowing how to make it happen are two different skill sets. And right now, one is missing.

The current MAHA leadership may be sincere in their intentions—and they have well equipped experts in health advising them on substantive issues. (We are blessed to have incredible experts in true health with the bravery to speak up!) What we lack is the infrastructure and process required to deliver sustainable change at the system level.

That’s why trust is eroding. Because people sense—rightly—that there’s no “how” behind the “what.”

It’s ironic: the same people who once fought against “trust the experts” and “trust the science” are now asking us to “trust the process”—without ever showing us one.

We’re told to trust that AI-powered systems will revolutionize chronic disease. To trust that Palantir’s deepening role in HHS surveillance is for our own good. To trust the MAHA Commission. To trust that this time, somehow, it’s different.

But branding isn’t a blueprint.

When decisions lack evidence, goals, and accountability mechanisms, it’s not a process—it’s a persuasion campaign. That’s not public health. That’s politics.

For those of us (myself included) who genuinely trust RFK Jr., this can be hard to face. But personal loyalty isn’t a substitute for structural accountability. We don’t build movements on vibes—we build them on integrity. If we want Bobby to succeed, we have to row with him—not just cheer from the shore. Because no individual, no matter how principled, can swim against the current of a corrupted system alone.

Support without scrutiny is not loyalty—it’s negligence.

So let’s be clear: If we believe in this mission, we must demand the process—not assume one exists. Blind trust won’t take us upstream. It’ll row us straight over the waterfall.

Trust isn’t built on buzzwords. It’s built on behavior.

And so far, MAHA hasn’t earned it.

The Importance of a Systematic Process

The cost of skipping procedural best practices is time—and time is not on our side. In public health, there’s a well-known statistic: it takes an average of 17 years for research findings to be fully integrated into real-world practice.

Think about that: if HHS were to determine tomorrow that the childhood vaccination schedule contributes to the rise in chronic disease, it would take roughly 17 years for the average physician to stop recommending it.

Absurd, right?

Why not just pass a law?

Well, first—our congressional process is famously slow 🙄. Second, even the most seemingly “simple” policy changes are anything but simple. Take the transition from paper medical records to electronic health records (EHRs). The only change was moving from a clipboard to a computer. That shift took over 16 years, cost more than $30 billion, and still isn’t fully operational.

That delay isn’t just bureaucratic drag—it’s what happens when system change isn’t done well.

It reflects the cost of skipping implementation best practices: failing to engage stakeholders, rushing past structured planning, and neglecting the infrastructure needed to support change.

Change is slow—but it doesn’t have to be this slow.

There’s an entire science—implementation science—dedicated to accelerating change without sacrificing integrity, accountability, or effectiveness. We know how to do this. The only question is: will we?

What A Gold Standard Process Looks Like

So what does it really take to build trust? To move from slogans to systems?

Decades of research on how to translate science into real-world impact point to the same conclusion: real trust is not declared—it’s built. It comes from transparency in how decisions are made, accountability for outcomes, genuine community engagement, and rigorous use of data to guide action.

This isn’t guesswork. It’s science. And the roadmap already exists.

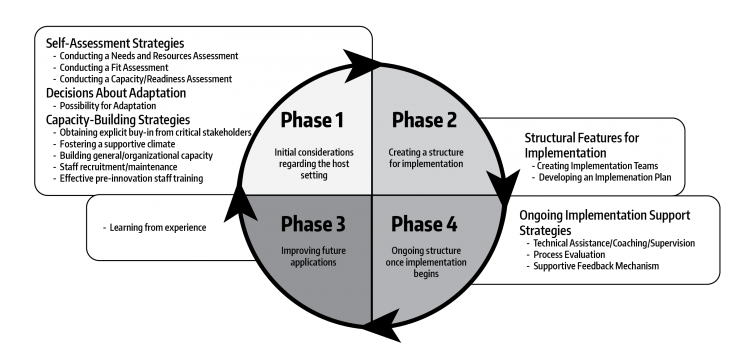

There are dozens of well-established frameworks (some of which I’ve co-developed) that lay out exactly how to do this. I won’t bore you with citations and jargon—but if you’re the visual type, check out the synthesis from my colleagues Meyers, Durlak, and Wandersman. It distills what works.

Despite noble goals, most large-scale reforms fall short—because process is everything.

There are four well-documented reasons health efforts fail to reach desired outcomes:

The idea was flawed.

The implementation was poor.

The initiative wasn’t adequately supported.

The outcomes weren’t effectively evaluated.

Any one of these can derail even the best intentions. When all four are ignored? Failure becomes inevitable.

And that’s where MAHA is faltering.

The leadership is asking us to trust them—but how can we trust a process that either (a) hasn’t been built using gold-standard methods, or (b) hasn’t been communicated transparently to the public?

Either way, it’s a betrayal of the very promise MAHA was built on: system change grounded in gold-standard science and governmental transparency.

Let’s Make This Concrete: Cracks in the Foundation

Much of the current backlash on social media—the confusion, frustration, and outright skepticism—isn’t irrational dissent. It’s a signal of poor process.

We can’t trust a process that we can’t see, especially from a group that promised transparency.

When people question why wearables and food dyes were prioritized over mRNA technology or the childhood vaccine schedule, they’re not being contrarian—they’re asking the right question: How were these priorities selected? Why are some of the most destructive and contentious drivers of chronic disease being ignored?

The public isn’t rejecting science. They aren’t rejecting the premise that food matters or wearables can be helpful to some. They’re rejecting a process that feels selective, opaque, and agenda-driven.

In any quality improvement effort, the starting point is clear: a rigorous, well-designed needs assessment. Yes, the MAHA Commission did release one. But the process behind it was so thin, so cherry-picked, and so poorly executed that it failed to do what needs assessments are designed to do—uncover the full scope of the problem, across populations, perspectives, and systems.

This wasn’t a blueprint. It was a press release.

This is where a mid-course correction could be made to get MAHA back on track.

To be effective, a real needs assessment should:

Define the problem with specificity and nuance

Use mixed methods to capture diverse voices—including parents, practitioners, scientists, and marginalized communities (including the injured)

Gather data across subpopulations to understand whose needs are greatest and why

Examine the full range of structural, systemic, and cultural barriers to change

Review the state of the science—not just what’s known, but what remains unknown and contested

Clearly outline gaps in services, outcomes, and infrastructure

It also must assess the context in which change must occur. What are the legal, policy, and regulatory barriers standing in the way? What are the dominant cultural narratives, the organizational dynamics, the political landmines? What role do professional associations, private interests, and media ecosystems play in suppressing or promoting certain solutions?

The MAHA Commission did none of this.

They didn’t collect new data. They didn’t establish a baseline of chronic disease burden or disaggregate it by type, population, or outcome. “Chronic disease” is an umbrella term—but which conditions are driving the greatest loss of life, quality of life, and economic burden? Which are most preventable, or reversible? Which are worsening fastest—and in which populations? Perhaps most importantly: why is this happening—and to whom?

They also didn’t identify or inventory existing programs, initiatives, and infrastructure that could be leveraged. A true needs and resources assessment must not only identify gaps—it must also map assets to avoid duplication and inefficiency. This process should include a systematic review of what’s already being done to reduce chronic disease, by whom, and with what results. What’s working? What’s failing? What’s missing? This is where MAHA had a chance to point out the limitations of the pharmacetical approach, the parental reports of vaccine injury, the worsening state of health despite increased costs. This is where the foundation for change could have been set. It was an opportunity missed.

Additionally, there was no prioritization framework for needs or conditions. No explanation of how decisions were made, or based on what criteria—leaving the door open to charges of arbitrariness or political favoritism.

Further, there was no alignment with federal agency levers. An effective assessment should connect findings to actionable levers within HHS agencies. What can CDC, NIH, FDA, CMS, or ACF do differently based on these findings? That vital step was missing. The findings were not embedded within context.

None of these questions were answered. And without those answers, it’s impossible to set goals that are specific, measurable, or time-bound.

To be clear: the content of the report was not the issue. It spotlighted risk factors often ignored by mainstream health agendas. It was well-written and compelling—for an OpEd or policy advocacy piece. The content contributors did what was asked, and they did it well.

But what was needed was a Needs & Resources Assessment, not a policy manifesto. Because the Commission didn’t follow appropriate methodology, the result was a document full of gaps and omissions. The report contains compelling ideas—but without methodological rigor, it lacks the foundation for any transformative process.

The lack of a quality needs assessment is like laying a foundation without surveying the land—the entire structure was doomed to crack before the first brick was placed.

If the proper methodology was followed, it would have led to a trustworthy process that offered:

Short-, medium-, and long-term goals tailored to subpopulations and connected the dots between initiatives

A clear theory of change and logic model showing how the goals will be achieved

Evaluation strategies for both implementation and outcomes so success could be demonstrated

Priorities for NIH research based on identified unknowns and areas of controversy

Cross-agency alignment with policy levers across CDC, FDA, ACF, and others based on systemic barriers to change

That’s how we build a system people can believe in. That’s how you move from slogans to structure.

We don’t need another poster campaign or celebrity endorsement. We need a transparent, accountable, evidence-informed roadmap.

That’s the process we could trust.

A Course Correction Is Still Possible

It’s not too late to start again—and this time, do it right.

MAHA’s mission resonates with millions because it speaks to real pain, real urgency, and real hope. But good intentions alone won’t drive lasting change. We need a structure that matches the stakes. That’s why it’s time to bring in the people who do this for a living — the experts in evaluation and strategy. It’s time to up the stakes.

The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) within HHS has both the expertise and the mandate to lead rigorous, nonpartisan evaluations. These professionals are trained in policy analysis, systems thinking, and evidence-based planning. This is not a job for influencers or PR strategists—it’s a job for public servants who know how to design, assess, and steward systemic change.

Once the goals and strategy are clear, we absolutely need professionals trained in marketing, behavioral science, and message testing to ensure communication is transparent, honest, and actually understood.

Consultant groups like the Global Health Project (which I am a founding Board member — shameless plug!) have deep experience conducting assessments of public perception and translating complex public health strategies into language that resonates across diverse communities. Understanding how people resonate can help drive strategy.

Handing the reins to ASPE and GHP wouldn’t be a step back—it would be a bold, strategic pivot toward credibility. A sign that MAHA is willing to be held to the very standards it promotes. That would rebuild trust far faster than another round of slogans ever could.

We still believe in the mission. We still want this to work. But we need more professionalism, more clarity, and more communication. Not to divide the movement—but to strengthen it. Because when we get the process right, the outcomes will follow.

That’s not criticism. That’s commitment.

We cannot allow MAHA to fall short. Our children’s lives depend on it.

Let’s build something worth trusting. And let’s do it together.